Geographers tell us that some forty million years ago, when the Indian Continental Plate steadily moved north and collided with its Asian counterpart, it triggered the creation of the Himalayas.

Four giant crisscrossing mountain ranges: the Himalaya, Karakoram, Pamirs, and the Hindu Kush, formed an unprecedented concentration of the loftiest peaks and largest glaciers which have given birth to the most picturesque meadows, valleys, and lakes.

The mule tracks and dirt roads that ultimately became KKH can be traced back to the Han Dynasty of Ancient Chinese Civilization during 207 BCE-220 BCE. Tradesmen used these winding ‘silk routes’ to carry their wares – silk being the most precious of these – from one side of the continent to the other.

There were four major trade routes called Northern, Southern, North Western, and Maritime Silk Route. KKH is the modern expression of what was once the “Southern Route” connecting Ancient China with the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Northern tip of the Syrian Desert, and the Mediterranean.

It was linked with the Italian peninsula through the sea route. Before the division of the British Indian empire into the new states of India and Pakistan, the Northern Areas were accessible to travelers only through two routes, the “Srinagar–Astore–Gilgit” mule track and the “Kaghan Valley” route crossing over the Babusar Pass to Chilas and Gilgit.

After 1947, the only option left within the new state of Pakistan was the Kaghan route, which unfortunately was only open four months of the year due to the severity of the weather in the region. Heavy snowfall, avalanches, and frequent land sliding left these areas inaccessible to the rest of the country most of the year.

These were the challenges of geography and climate that created the desire for what became known as the “Friendship Highway”. Traversing mountains above the height of four thousand meters (4714 meters, at highest point), KKH is one of the world’s highest paved roads, a marvel often declared as the eighth wonder of the world.

The Pakistani and Chinese engineers built it on their respective sides. One story, as narrated by Lieutenant Colonel Tanveer Hassan Bashir, Staff officer to Engineer-in-Chief during 1965-66 states, “the road link was suggested by China during the period

of Major General Nawabzada Agha Muhammad Raza, Ambassador of Pakistan to China (1962-1967) on the pretext that China is extending its road network till the China – Pakistan border, so should Pakistan for a road link between the two countries.

However, the idea was kept secret from the USA due to close ties with Pakistan. However, Americans not only abandoned Pakistan but also embargoed supply of war material during 1965 War; contrary to that Chinese all-out support further cemented the idea which ultimately led to the construction of this marvel.

” Another account is given by a letter of Mr. Ghulam Faruque, Commerce Minister of Pakistan (1964-67), who suggested PM Zhou Enlai the shortest trade route for trade with the Middle East. Wherein he asked for a map, and this time, FM Chen Yi was also present.

After looking at the map, the FM said, “when can we start.” It is in this historical context that the KKH was conceptualized to develop a highway with the dual purpose of internal and external connectivity; within Pakistan and through the Khunjrab Pass connecting Pakistan with China.

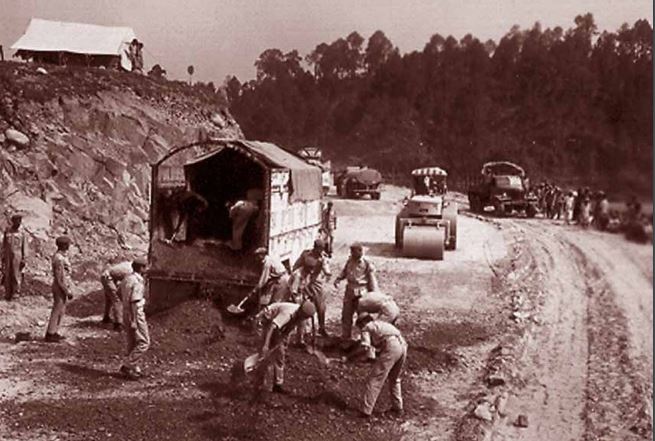

With the technologies of 1960’s it was almost an impossible task; death, despair, and incredible hardship was endured along almost every stretch of KKH during its construction leading to the loss of more than a thousand workers.

Birth of FWO

After a formal agreement with the Chinese to construct the road, the Government of Pakistan assigned this arduous task to the Pakistan Army’s Engineering Corps. The decision was to raise a composite organization to manage all aspects of this challenging construction; FWO was thus born.

It was raised in 1966 along with two groups, the 491 Road Construction Group (RCG) and 492 RCG. The 491 RCG had three road construction battalions, namely 102 RCB, 103 RCB, and 104 RCB. It also had 3 x Pioneer Battalions (152, 153, and 154 Pioneer Battalions).

In contrast, 492 RCG had only one battalion, 105 RCB. From this humble start in 1966, FWO has progressed since then to become one of Pakistan’s largest engineering and construction firms.

Given its specialization in all aspects of engineering, bridge construction, tunneling, and its ability to deliver in areas of hostility, FWO has emerged as a national strategic organization.

Over the years, the FWO has gone on to work on hundreds of diverse projects across the country; from KKH to the Makran Coastal Highway in Baluchistan, its handiwork is visible everywhere.

In recent months, responding to the challenge of the pandemic, it built Isolation Hospital and Infectious Treatment Center (IHITC) in Islamabad in a record 40 days. FWO is now international; it has also gone on to successfully undertake international construction projects in Kuwait, Afghanistan, Liberia, and the UAE.

KKH: Phases of Construction

In 1948, a 198 km stretch of the mule track was upgraded by Royal Pakistan Engineers, which allowed jeeps to travel up to Chillas, and between 1958-66 work was done on a further 400 km Indus Valley Road connecting Swat with Gilgit. But the real serious work started on the KKH after the formal agreement between Pakistan and China.

Pakistan initially favored routing the construction through the Mintaka Pass due to low elevation and year-round accessibility. However, the Chinese felt that the Mintaka Pass would be more susceptible to the Soviet Union airstrikes. The Chinese recommended the steeper Khunjerab Pass instead, which was agreed by Pakistan.

Construction began in 1966, and the road was divided into two Sections: Thakot to Chillas as Section I and Sec II from Chillas to Khunjrab Pass. 492 RCG was assigned Section I, while Section II was assigned to 491 RCG.

The highway was finally completed in 1978 and had the sad record of losing more than one worker every km while carving through the towering mountains, glaciers, and isolated valleys to build 806 km long Karakoram Highway to connect with China.

Out of 723 Km of the highway from Havelian to Khunjerab, FWO constructed 579 km up to Hallegush. FWO has the unique honor of not only constructing but also maintaining KKH operational to date. Over 800 Pakistani and 200 Chinese workers lost their lives

during the challenging construction of the highway.

KKH: Importance and impact

KKH traversing through the world’s highest mountain ranges contributed to the integration of the Gilgit-Baltistan region with the rest of the country and helped to promote national and regional integration through road networks. It has affected the domestic, regional and global landscape in many ways.

It has helped promote tourism, especially adventure tourism and trade, and employment opportunities for locals have increased. GB is rich in minerals and hydropower, and the construction of KKH has made it possible to explore this potential by making the sites easily accessible.

The highway allows the transport of emergency supplies from China, from defense to life-saving items, should they be needed. It has opened new vistas for bilateral/ transit trade with China. KKH has also frustrated Indian designs by ending GB’s isolation and by fully integrating this region with areas below in Pakistan.

But KKH’s real potential remains unrealized and awaits further developments. China, the North-Eastern region of Afghanistan, Iran, and Tajikistan, if connected through Wakhan Strip, can utilize the KKH as a trade corridor, thus creating opportunities, being the shortest route to the Arabian Sea.

With CPEC becoming a reality, KKH also promises to be the cornerstone of Central Asian and South Asian connectivity. This has already enhanced the strategic and economic importance of the KKH manifold.

As an alternate, shorter and safer route for China to reach out to the Middle East, Europe, and Africa, Chinese trade has the option to bypass the bottleneck of the Strait of Malacca. However, to reap maximum benefits from KKH, in the context of CPEC, thorough planning is needed both for its optimum utilization and any future development.

KKH and future of CPEC

Implications of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) are well known; it has often been described as a game-changer for Pakistan that, if correctly utilized, can boost

the economic and geopolitical role of Pakistan in the region.

CPEC as a multi-billion dollar project encompasses road and rail infrastructure and cooperation in energy, agriculture, science, and technology between China and Pakistan. If properly executed, it can reap rich dividends for both countries.

KKH is the backbone of the project connecting Kashgar to Gwadar Port, Pakistan’s crown jewel, and giving China access to the warm waters of the Arabian Sea, offsetting potential threats in the Malacca Straits. A significant portion of KKH, conceived in 1960’s, goes through GB.

CPEC, the flagship project of China’s One Belt One Road Initiative (BRI) is now also passing through this region, and the multi-purpose Diamer-Bhasha Dam is also being constructed in this region.

However, since the formal announcement of the CPEC project in 2015, anti-CPEC and anti-Pakistan international lobbies – India – have been busy trying to make all significant development projects controversial by constantly disputing the legal status of GB to try to undermine Pakistan’s credentials to administer and develop the region legally.

This is a challenge that Pakistani media and intelligentsia must meet. Any road infrastructure project in a mountainous region requires regular maintenance. Delaying the routine maintenance and up-grading of KKH can aggravate the situation as a substantial portion of the road, especially between Chillas and Dassu, is deteriorating.

This situation creates genuine resentment and is also being exploited by certain elements. The good news is that as part of CPEC projects being executed all over Pakistan, the Havelian-Thakot highway section has been completed.

However, there is little or no visibility in the public domain about the future of KKH as a transit trade route. While Government continues to claim expansion of CPEC’s projects,

the public, especially in the GB Region, is not much aware of any rail link and pipelines for connectivity with China.

This lack of clarity is likely to induce a sense of uncertainty, especially among locals and foreign investors. KKH, nevertheless, from its inception till date, remains a symbol of perseverance, courage, and optimism for China and Pakistan. It has all the potential to become the future silk route in this region with its past inheritance and glory.

The picturesque valleys, breath-taking landscapes astride the highway, and global power politics give this region a multi-dimensional importance. Challenges and opportunities will continue to present themselves in parallel dimensions. But all required components for making this highway a strategic road at the global stage are there. All we need is seriousness of purpose, sincerity of effort, foresight, and endeavor at national level to transform this dream into reality.